by Eve Johnson

The day I met my first yoga teacher, Wende Davis, she placed me in Right Angle pose (which some call Half Downward-Facing Dog pose) with my hands resting on the top of her upright piano and ran her fingers along my spine. When she came to my upper back, she tapped and said, “That’s where your work is.”

And that’s where my work stayed for the next 29 years. In countless yoga classes, workshops, and teacher trainings, helpful fingers tapped my back in the same spot to bring awareness into my stiff and overly rounded thoracic spine. I was told that my tendency to round was genetic, but with practice I could slow down, or even stop, the increasing curve. The genetic part made sense because my mother and my older sister were both more rounded than me.

So, in class and at home, I worked on it. I had a daily practice of chest openers. I studied backbends. Moving slowly and with focus, I learned to lengthen my spine and draw in my thoracic vertebrae. Eventually, I could change the shape of my upper back in a pose so it was less rounded.

After 13 years as a student, I started teacher training and eventually passed my Jr. 1 Iyengar certification. But helpful fingers continued to tap my spine. In deep forward bends, my back still humped. In candid photos I saw myself getting shorter and more rounded every year. And I used to feel upper back pain after long walks, hours of standing in the kitchen, and extended seated meditation.

Then in March, 2016, I took a weekend workshop in Spinefulness (Spinal Mindfulness) with Jean Couch and Jenn Sherer in Palo Alto, CA, led there by Thea Sawyer’s excellent book Put Your Back at Ease. Jean is a former Iyengar yoga teacher, the author of the Runner’s Yoga Book. She’s also one of the voices you hear on the NPR story on healthy bending that Nina and Baxter have been writing about.

For the first time, I learned why my back rounded and how to straighten it. I learned that posture is cultural, and that although every woman in my family had a rounded upper back, our genes weren’t the problem. Like all little girls, we had modeled our posture on our mother’s, and achieved the same results.

I learned new habits: sitting with my weight as far toward my pubic bone as possible, turning my feet slightly out instead of keeping them parallel, releasing my chin, and elongating the back of my neck. More problematic, I had to unlearn habits, such as locking my knees when I stood and, most of all, lifting my chest. It was counter-intuitive, but true that when I stopped trying to sit up by lifting my sternum, I became straighter.

Over those two days, my new alignment began to feel right. Sitting, I found myself in an unfamiliar state of equanimity, both elevated and relaxed, neither slumped nor on edge. Late on Sunday afternoon, Jean’s hands gently guided me into alignment. My spine lifted, my ribcage lengthened, and my back ribs moved up and forward. I had never before felt so light, or so clear.

I’ve been back to Palo Alto four times since then, and am completing certification for teaching Spinefulness this summer. My spine has visibly straightened. I can avoid humping my back in forward bends. I no longer feel doomed to hunch over as I age. And I now rarely feel upper back pain after my long walks, hours of standing, and seated meditations.

On the left is my photo from March, 2016. Notice that my knees are locked and my belly protrudes. Also, my thighs are well ahead of the line, and my upper back rounds behind the line. On the right is my photo from January, 2018. I still have a long way to go, but my weight has moved to my heels, my knees are soft, my belly doesn’t stick out and my thoracic spine is longer and straighter.

In the yoga classes I teach, students whose upper backs have always humped in forward bends are learning to elongate. Other students report that chronic tightness in their quads and hamstrings has released, and sore backs, knees, and feet all improve. What’s the secret? What technique could possibly be so universally helpful? Spinefulness teaches us to align our bodies in their most efficient relationship with gravity, as we did when we were toddlers and as some people in less industrialized cultures still do.

We all know that a building can’t stand if one of the columns curves at the base, and that a bridge will collapse if its supports don’t transfer its weight efficiently into the ground. But, we rarely remember that human beings are physical structures, in essence a bridge that walks. People who live in industrial societies are almost universally out of line with gravity. Starting about the age of three, when we begin to imitate the adults around us, we take our pelvis, our center of gravity, forward of the gravitational line. Modern pelvis-forward posture is a result of many influences, including baby seats that curve infants into a C-shape, bucket seats in cars, soft couches that encourage us to round our backs, and a culture of sitting for hours at a time, with our buttocks tucked under and our spines rounding.

And then there’s fashion. Before 1920, many more of us stood in alignment. Then came the flappers, who made it cool to stand with the pelvis forward. Decade by decade, that trend has continued and intensified.

|

Even Steve McQueen, the coolest of all, can’t escape the consequences of sitting back on the buttocks: a rounded spine with head thrust forward.

Once our center of gravity is off-center, every joint in the body has to compensate. To balance our forward pelvis, our upper body moves back and rounds. To complete the counter balance, our head moves forward. With the pelvis forward, we take more weight than nature intended into our feet and knees. When we sit, we tuck our buttocks under. Our back rounds into a C-shape, and our head juts forward.

This means that the weight of our bodies no longer moves through our bones. Instead we decommission the bones and depend on our muscles to hold us up. But bones evolved to bear weight. Muscles evolved to move the bones. (An exception would be the deep core muscles closest to the spine.) So when we ask our muscles to hold us in an out-of-balance position, the result is tense, gripped muscles—a tension we are so accustomed to that we rarely feel it until it reaches the point of pain.

Because we spend most of our waking hours out of balance, either sitting or standing, no yoga practice, however faithful, can possibly undo the rounding. Even two hours every day is no match for 22 hours of off-balance posture. (Yes, Spinefulness teaches us to sleep in alignment, too.) As Jean Couch likes to say, “you can turn the lights on and off, you can turn the heat on and off, but you can’t turn gravity off.”

So how do we find our healthiest relationship to gravity? We imitate people who live in balance. They have a short, sharp arch low in the back and an elongated, almost straight spine. They also have bones that stack—with pelvis, spine, and ankles all in one line—and soft, elastic muscles.

|

| Standing with weight in heels and pelvis back |

|

| Letting pelvis hang forward, creating a zigzag line in the spine |

The first step is to sit on our bones and relax.

How to Sit

Sitting with Spinefulness entails the “figging” motion that Nina and Baxter have written about in their posts Life-Changer: Bending Over Differently and Time to Rethink Standing Forward Bend. Sitting is, of course, a variation of bending, so the instructions are much the same. As you sit down, you bend your knees and allow your pubic bone—the place where Adam and Eve wore their fig leaves—to move between your legs, going both down and back toward the wall behind you. Ideally, you sit with your weight falling into your pubic bone. But correcting misaligned posture is a process, and for most of us, sitting forward on the sitting bones is enough to start with. Once we rotate the pelvis forward, we’re able to form our natural arch at L5/S1 (just above the top of the sacrum, where it connects to our lower spine, the lumbar) We also immediately deepen our lower spinal curve, the lumbar curve, above the natural arch.

Next, seated with your upper back touching the back of your chair, relax your buttocks. Then relax your upper body, letting your sternum and your front ribs descend. (If you’ve spent a lifetime trying to lift your chest to stand up straight, you might feel like you’re slumping.) To feel longer and lighter, you need to lengthen your spine. The Spinefulness solution is a “chair hitch”:

- Pull your feet back toward you, so you won’t be tempted to lift from your legs. Hold on to the sides of the chair and push down. Without lifting your pelvis or the front of your chest, draw your lower belly toward the small of your back and up.

- Once you have your maximum lift, curl back, with your chest still down, to place your upper back on the chair. Relax your shoulders and lift your head.

- In a successful chair hitch, your back will connect to the chair higher than before you started. Check that your buttocks are still relaxed, and your chest is still soft.

With the chair hitch technique, you use your abdominal muscles to pull the bones of your low back toward the back of your body. This means that the bones are better able to stack, with your body weight transferring down the flat, thick bones at the front of the spine. Imagine the spine as a column, and then see the exaggerated curve that many of us have in our lower backs. With the lumbar spine forward, the bottom of the column is no longer in line with the top. And without support, the top of the column sinks. When the bones of the low back move back in place, the upper spine feels light. It becomes longer and more mobile.

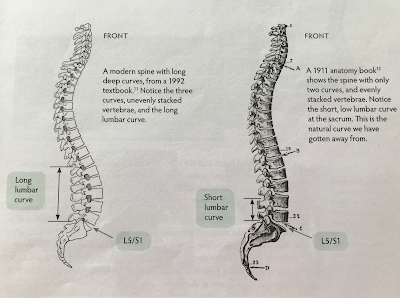

Take a look at the two spines below. In the 1911 example, the bones of the low back rise almost vertically from the short, sharp arch at their base. The upper back is also less curved. It lines up with the lumbar vertebrae, the support bones of the bow back. In the 1992 example, the bones of the upper back sit so far behind the lumbar, that they lose the support of the bones beneath them.

In the spine on the right, the more stacked vertebrae are able to support the thoracic spine in the upper back. In the spine on the left, there’s no support for the upper back. (From Thea Sawyer’s book Put Your Back at Ease, used with permission.)

The way we spend our days shapes our bodies, which can be bad news if your job requires long periods in a chair. The good news about Spineful sitting is that once you “fig” and relax, your sitting time can actually help relieve back pain, and improve your posture. There’s a catch, of course. Spinefulness is an awareness practice and awareness is fleeting. So you will still catch yourself slumped in a C-shape with your shoulders around your ears and your head craned forward towards a computer screen. But now you’ll know how to fix it.

Changing Our Habits

Perhaps the most difficult part of Spinefulness is to undo our ideas of good posture and stop lifting the chest. We’ve all been reminded countless times to “stand up straight,” meaning pull the front chest up and the shoulders back. Sadly, the longer you’ve practiced yoga, the more likely it is that lifting your front chest feels natural and good. We’re so used to the strain it causes that we no longer feel it— at least until we’ve been taught to relax.

But lifting the front chest shortens the back and takes us out of our most efficient relationship to gravity. The spine evolved to bear weight through the vertebral bodies, the front part of the spine. When we lift the front ribs, we pinch the lower back and transfer weight into the spinal processes at the back of the spine. And once we’ve lifted the front ribs, it’s impossible to lengthen the spine.

True length in the spine comes from keeping the front ribs drawn toward the spine and from lengthening the back and side ribs to our full extent. Once that length is present, the elongated upper spine, the thoracic, is free to move towards the front of the body.

How Does Spinefulness Fit with Yoga?

In a word, seamlessly. Using Spineful alignment in my asana practice brings new ease into my poses. Twists are freer. I can access my upper back better in backbends, which makes them less stressful for my lower back. And because I can now lengthen my spine more effectively, my forward bends are less curved.

This probably shouldn’t be surprising. For one thing, Spinefulness has deep roots in yoga. In 1959, Noëlle Perez, the Parisian genius who did the research that underlies Spinefulness, became one of BKS Iyengar’s earliest European students. She continued to study with him into the 1970s, and eventually published Sparks of Divinity, a collection of his teachings. Noëlle struggled with pain, particularly in Headstand. And she credits Iyengar’s advice with giving her the first clue to what became her life’s work.

“Walk behind Indian women and observe them closely, copy them,” Iyengar told her. “When your shadow matches theirs, you will have made progress.”

In India, before the onslaught of western culture, a relaxed, aligned way of sitting, standing and walking used to be close to universal. I like to think that when I bring my body into its best relationship with gravity, I too am making progress.

If you are interested in learning more about Spinefulness, you can experience Spinefulness with Jean Couch this summer in Vancouver, Canada, where she will teach a weekend immersion course July 7 and 8, and a 30-hour intensive July 9 through 13. For more information, go to yogaon7th.com. If you live in the San Francisco Bay Area, you can contact Jenn Sherer, at spinefulness.com and check out workshops at spinefulness.com/workshops.

Eve Johnson is an Iyengar Yoga and Spinefulness teacher based in Vancouver, Canada. She owns and teaches out of Yoga on 7th studio in Vancouver. Eve’s focus has always been on encouraging her students to develop a home practice. Until an intense bout of Spinefulness training intervened, she wrote the My Five Minute Yoga blog, subtitled “friendly advice for growing a home yoga practice.” She plans to return to blogging soon. In the meantime, she’s relishing the constant opportunities for practice that Spinefulness provides.

Follow Yoga for Healthy Aging on Facebook ° To order Yoga for Healthy Aging: A Guide to Lifelong Well-Being, go to Amazon, Shambhala, Indie Bound or your local bookstore.

Leave A Comment