by Nina

|

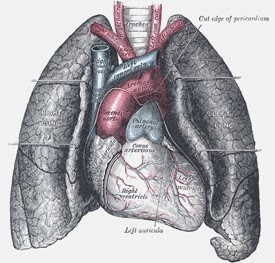

| Heart and Lungs |

I hope you realize by now that there are a lot of myths out there in the yoga world, such as that yoga nidra is an ancient practice or that Sun Salutations have been practiced for thousands of years. So here at Yoga for Healthy Aging, we try to do a bit of fact checking before we go ahead and write about a subject, whether it is medical, scientific, or historical. And when I edit a post, I try to confirm anything that looks a bit, well, suspect. But once in a while, I’m less than meticulous, and that can result in an error or two. After I read what Baxter wrote about the relationship between the breath and the nervous system in his post How Your Breath Affects Your Nervous System, I asked him to take a look at a related post I wrote some time ago called Your Key to Your Nervous System: Your Breath because I was concerned that perhaps my original post had errors in it. Although at the time I had been writing about what I was convinced were facts, Baxter confirmed that some of the information in my post about yawning and the affect of the breath on the nervous system, which I had learned from a yoga teacher, was actually incorrect. Baxter identified this misinformation as a yoga myth—ideas that seems to get perpetuated, despite the fact there is no proof of their validity.

So this post today is an update to my original post, with Baxter’s comments/corrections on my original statements. Well, it’s a journey for us, too, right?

YOGA MYTH: Nina wrote, “Have you ever wondered why you tend to yawn when you’re sleepy? Well, a yawn is a great big inhalation. And because your heart rate tends to speed up on your inhalation, that yawn in the middle of that boring lecture or business meeting is little message to your nervous system: wake up! On the other hand, when you are upset about something, you tend to sigh. That sigh—try one!—is an extra long exhalation. Because your heart rate tends to slow on your exhalation, that sigh while you are feeling emotional turmoil or are just stuck in traffic is a little message to your nervous system: take it easy, buddy, slow down a bit.”

BAXTER’S CORRECTION: Here’s what I found…and it does not seem to confirm your suggestions that it is the heart rate effects that are driving the yawn or sigh. There are four theories about why we yawn, none proven or much studied:

- Physiologic theory: Our bodies induce yawning to draw in more oxygen or remove a buildup of carbon dioxide. At least one studied seems to have disproved this theory.

- Evolutionary theory: Some think that yawning began with our ancestors, who used yawning to show their teeth and intimidate others. An offshoot of this theory is the idea that yawning developed from early man as a signal for us to change activities.

- Boredom theory: Although we do tend to yawn when bored or tired, this theory doesn’t explain why Olympic athletes yawn right before they compete in their event or why dogs tend to yawn just before they attack. It’s doubtful either is bored.

- Brain-Cooling theory: a more recent proposal is that since people yawn more in situations where their brains are likely to be warmer—tested by having some subjects breathe through their noses or press hot or cold packs to their foreheads—it’s a way to cool down their brains. Cool brains think more clearly.

Why do we sigh? As it turns out, sighs do seem to work like the brain’s reboot button for regular breathing. According to a 2010 study Take a deep breath: The relief effect of spontaneous and instructed sighs, during mental stress, the volunteers’ breathing became more and more irregular as participants increasingly relied on deliberate breath control, at which point, a sigh occurred, causing automatic regular respiration to kick in again. Furthermore, muscle tension steadily built up before a spontaneous sigh and decreased afterward, supporting the idea that sighing helps release tension.

YOGA MYTH: Nina wrote, “It turns out that by intentionally taking in more oxygen (either by speeding up your breath or by lengthening your inhalation) you can stimulate your nervous system and that by taking in less oxygen (by slowing your breath or lengthening your exhalation), you can calm yourself down. It’s that simple.

BAXTER’S CORRECTION: It is actually likely not that simple, as the effect I described in my post How Your Breath Affects Your Nervous System really more clearly explains what happens: the inhale speeds up the heart rate (not because of O2 levels) and the exhale slows it down (not due to O2 levels, but due to the nerve input from breath cycle to heart). As the heart rate slows more over the course of five minutes of 1:2 ratio breathing, for instance, the slower heart rate is monitored by the brain and leads to even further turning on of the parasympathetic Rest and Digest response. And, in fact, carbon dioxide levels in the blood stream have a much greater influence on the rate of breathing than O2 levels, and are monitored much more closely by the brain moment by moment and lead to adjustments in the ANS tone of whether sympathetic or parasympathetic nerves are stimulated. The importance of “getting more oxygen” in is a myth that has been propagated for a long time by yoga teachers in this country. For further information, see Leslie Kaminoff’s article What Yoga Therapists Should Know About the Anatomy of Breathing.

CONCLUSION: Well, we’re all learning this stuff together. Even Baxter went ahead and did a bunch of new research. And, sigh, at least I was right about sighing.

Follow Yoga for Healthy Aging on Facebook ° To order Yoga for Healthy Aging: A Guide to Lifelong Well-Being, go to Amazon, Shambhala, Indie Bound or your local bookstore.

Nice to see some measured commentary. Yawning stimulates the precuneus structure in the brain, which correlates with self-awareness and some other functions. It makes sense that you would experience more yawning as you go within, and close out distractions of the normal daily environment.