by Nina

|

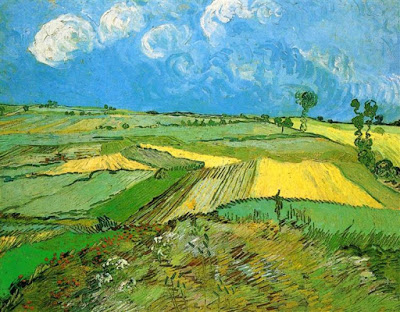

| Wheat Fields at Auvers Under Clouded Sky by Vincent van Gogh |

“The research shows for the first time that breathing—a key element of meditation and mindfulness practices—directly affects the levels of a natural chemical messenger in the brain called noradrenaline. This chemical messenger is released when we are challenged, curious, exercised, focused or emotionally aroused, and, if produced at the right levels, helps the brain grow new connections, like a brain fertiliser. The way we breathe, in other words, directly affects the chemistry of our brains in a way that can enhance our attention and improve our brain health.” —from Trinity College Dublin

I always wondered why we are most often taught to meditate by focusing on the breath. Obviously, as ancient yogis discovered, meditating on the breath is particularly effective at quieting the mind. But why is that? Eventually I came up with my own theory. But I’m not going to share that theory with you today because some researches at Trinity College Dublin had a much more interesting theory, and they went ahead and developed a scientific study to study it! The study Coupling of respiration and attention via the locus coeruleus: Effects of meditation and pranayama looked at the “neurophysiological link” between breathing and attention.They did this by measuring breathing, reaction time, and brain activity in the locus coeruleus, the part of your brainstem that produces noradrenaline, a hormone and neurotransmitter. (I’d say more about how they did the study, but frankly the original paper was somewhat impenetrable, and even though I usually glean some information from these types of papers, I’ve got nothing.

According to The Yogi masters were right—meditation and breathing exercises can sharpen your mind, the researchers discovered that your breath affects noradrenaline levels in your brain, with levels slightly increasing during the inhalation and slightly decreasing during the exhalation.

In general noradrenaline readies your body and brain for action but levels go up when you are, as they said, “challenged, curious, exercised, focused or emotionally aroused,” not just when you’re in danger. In fact, levels are lowest while you are sleeping and start to rise when you wake up and become active. So, some amount is needed just for you to go about your day!

We have discussed the effects of this hormone in our post Understanding Your Autonomic Nervous System noting how it prepares your body and mind for action by stimulating your heart to beat faster and stronger and slightly raising your blood pressure to improve blood flow, and by opening your airways so you can breathe more easily. In extreme situations—where serious action on your part is needed—this hormone is part of what triggers your fight-or-flight response. In this state, your sympathetic nervous system actually turns off the background functions of nourishment, restoration, and healing that are provided by the parasympathetic nervous system because these functions will slow you down.

In addition to readying you for action, noradrenaline also affects your ability to focus. Michael Melnychuk, the lead author of the study, says that both too much noradrenaline, which is present when you are stressed, and too little noradrenaline, which is present when you are sluggish, reduce our ability to focus. He says, however, “There is a sweet spot of noradrenaline in which our emotions, thinking and memory are much clearer.”

You know I kind of wonder about this. I learned from psychologist Dan Libby that in the fight-or-flight state, it’s not so much that you can’t focus but rather that you can only focus on certain things, that is, fight or flight strategies (see Stress and Your Thought-Behavior Repertoire). So perhaps the “sweet spot” happens when you’re relaxed enough to think clearly but at the same time not too sleepy or exhausted. Regardless, how do we get to that sweet spot by practicing breath awareness or meditating on our breath? Michael Melnychuk says:

“It is possible that by focusing on and regulating your breathing you can optimise your attention level and likewise, by focusing on your attention level, your breathing becomes more synchronised.”

This sounds like a kind of feedback loop that happens just on its own. When you focus your attention on your breath, even though you don’t intend to change it, bringing your awareness to it alone will likely slow it down and make it more even, which in turn increases your ability to focus on it, which in turn regulates your breath even more, etc.

Besides being a particularly effective meditation technique, there is a good possibility practicing breath awareness or meditating on your breath can help with our aging brains! According to Ian Robertson, the principal investigator of the study, the sweet spot you reach when meditate on your breath (mindfulness meditation) “doses” your brain with the right amount of noradrenaline to grow new connections between your brain cells, something that doesn’t happen when your levels of noradrenaline are too high or too low. As he says:

“Our findings could have particular implications for research into brain ageing. Brains typically lose mass as they age, but less so in the brains of long term meditators. More ‘youthful’ brains have a reduced risk of dementia and mindfulness meditation techniques actually strengthen brain networks. Our research offers one possible reason for this—using our breath to control one of the brain’s natural chemical messengers, noradrenaline, which in the right ‘dose’ helps the brain grow new connections between cells. This study provides one more reason for everyone to boost the health of their brain using a whole range of activities ranging from aerobic exercise to mindfulness meditation.”

Now, what about pranayama, the breath practices where you intentionally control your breathing rather than allowing it to settle on its own? If you consider that more noradrenaline is released on your inhalation than on your exhalation, you can see how making your inhalation longer than your exhalation would be stimulating and making your exhalation longer than your inhalation would be calming. This allows you to use your breath practices to simulate yourself, calm yourself, or balance yourself as we describe in Pranayama: A Powerful Key to Your Nervous System. The study’s author seems to recommend pranayama to help you self-regulate, just as we do:

“In cases where a person’s level of arousal is the cause of poor attention, for example drowsiness while driving, a pounding heart during an exam, or during a panic attack, it should be possible to alter the level of arousal in the body by controlling breathing.”

Of course, we know from experience that pranayama allows us to change our levels of “arousal.” What Melnychuk is adding to that here is that balancing your nervous system with your breath will affect your noradrenaline levels, which in turn, should help you find the sweet spot where your ability to focused is maximized. So, if you’re stressed out or sluggish, practicing pranayama to balance your nervous system before meditating on your breath seems like the way to go. If lack of experience with focusing is the only thing interfering with your ability to meditate, you could just go ahead and meditate on your breath.

It does seems possible, however, that a balancing breath (where the inhalation and exhalation are of equal length) would serve the same purpose as breath awareness. (Information on how exactly to get to that sweet spot either isn’t in the original paper or I just couldn’t find it. In the end, I was left with a number of questions!)

Ian Robertson, the principal investigator of the study, says the research shows that both these breath practices have a strong connection with “steadiness of mind.” With that term, he’s including not only attention but arousal (stress levels) and emotional control (related to stress levels). So that’s an argument for practicing both pranayama and meditation.

“Yogis and Buddhist practitioners have long considered the breath an especially suitable object for meditation. It is believed that by observing the breath, and regulating it in precise ways—a practice known as pranayama—changes in arousal, attention, and emotional control that can be of great benefit to the meditator are realised. Our research finds that there is evidence to support the view that there is a strong connection between breath-centred practices and a steadiness of mind.”

2.2 When the breath is disturbed, the mind is unsteady. When the breath becomes focused, the mind becomes focused and the yogi attains steadiness. —Hatha Yoga Pradipika, translated by A.G. Mohan and Dr. Ganesh Mohan

Follow Yoga for Healthy Aging on Facebook ° To order Yoga for Healthy Aging: A Guide to Lifelong Well-Being, go to Amazon, Shambhala, Indie Bound or your local bookstore.

The Three Part Breath is a secret weapon that helps people out when they're in a tight spot. It works, and nobody knows you're doing it.