by Timothy

|

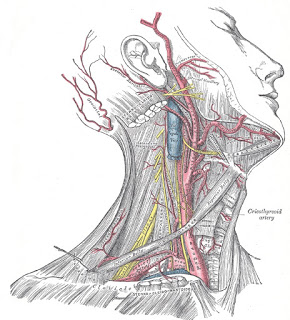

| Arteries of the Neck (from Gray’s Anatomy) |

There has been concern—and for some even fear—in the yoga community regarding the risk of strokes from doing yoga. How realistic is this?

Much of this fuss was set off by the New York Times writer William Broad, who warned that all the stretching of the neck in various yoga poses like Cobra and Shoulderstand could lead to tearing of the linguini-like vertebral arteries that run along either side of the neck bones, which could then lead to bleeding into the brain. But as I (and others) have written (see Man Bites Down Dog), Broad’s analysis was alarming, lacked data to back his extraordinary contentions, and in all likelihood was way off. Still, it may be worth discussing the risk of strokes and what thoughtful yoga practitioners and teachers can do to prevent them.

Vertebral artery tears and resulting strokes often happen when someone makes an unaccustomed neck movement. The example that is often cited is when an elderly woman drops her head back into the hairdresser’s sink. In such a case, the movement in question is an extension of the neck (the cervical vertebrae), not so different from what happens in backbends like Cobra pose and Upward-Facing Dog. But it’s also at least theoretically possible to tear the artery when you go in the other direction and flatten the neck vertebrae, as in Shoulderstand and especially Plow pose. Even twisting poses could cause problems if you crank the head too far. Outside of yoga, such strokes also have been reported to happen when people simply turn their heads to the side or suffer minor trauma. It is estimated that 1.5 people out of every 100,000 suffer vertebral artery-related strokes every year.

I have observed many yoga students who hyperextend their necks in poses like Cobra and others who flatten their neck in poses like Shoulderstand and Plow. In the case of backbends, many students have the habit of over-arching from the neck. They compress the backs of their necks, and often arch too much from the back of the skull (the occiput), at the atlas-occipital joint. (The atlas is another name for the first cervical vertebra.) This habit is common in those with tight thoracic spines. When the thoracic spine is stubborn, people sometimes overcompensate by overarching the more flexible cervical and/or the lumbar spines. In other words, when one link in the chain is tight, people tend to move more than they should from the links above and below it.

When instructing backbends, I encourage students to try to keep the back of the neck long. Rather than looking up in a pose like Cobra, I encourage those with the habit of neck hyperextension to keep their gaze forward, which tends to keep them from tipping the head back too much. It’s also useful to think of originating the movement in your neck from the middle of the thoracic spine and the lower cervical vertebrae (where the neck attaches to the back).

Poses like Shoulderstand and Plow pose tend to flatten the neck. This is especially problematic if the student tries to move the chin towards the chest (an unfortunate instruction that some yoga teachers use). Instead, I encourage students in these poses to lift the front of the chest toward the chin, and actually slightly move the chin away from the chest. If you try this, you may notice that it lessens the feeling of pressure at the back of the neck.

In the traditional hatha yoga Shoulderstand, known as Viparita Karani (not to be confused with the restorative pose that uses the same name), the legs are in a jack-knife position. In other words, the pelvis is behind the spine and the feet are forward of the spine. This pose can be done safely without any props, especially if you follow the instructions of moving the chin slightly away from the chest. This is the version of Shoulderstand I’ll do if I wind up somewhere with no props.

Rare is the yoga practitioner who is flexible enough to do the modern, more-directly vertical version of the Shoulderstand—in which the legs are stacked directly over the hips and shoulders—without blankets or other props to raise the shoulders off the ground. To keep suppleness in your neck, the number of blankets required varies. For example, I use four folded blankets under my shoulders. Try to place your shoulders near the edge of the folded blankets so you graze the skin over C7, the lowest cervical vertebra, while you work to lift C7 away from the ground. Your breath should be soft, slow and even throughout the pose, and if at any point you can’t breath smoothly, or otherwise feel uncomfortable come down.

Plow pose is even more challenging to the neck, and I recommend the same blanket set-up. If you notice any discomfort at the back of the neck, however, I recommend either skipping the pose entirely or placing your feet higher, for example, on the seat of a chair.

In twists, try not to lead with your head. In other words, the turn should come from the vertebrae all along your spine, with no twist whatsoever from the atlas-occipital joint. One instruction I give if students feel any tension in the neck is to turn the head ever so slightly (say 1 millimeter) in the opposite direction of the twist. What this accomplishes is to stop people from trying to twist the skull on C1, a motion those joints are not meant to do. Even more conservative, is to not let the chin turn any more than the chest, in other words the nose and chest point in the same direction.

Beyond lessening the theoretical risk of a vertebral artery stroke, all the above advice will also tend to help avert yoga’s contributing to such musculoskeletal problems of the neck as arthritis and overstretching of spinal ligaments. Indeed, averting these problems is actually my primary reason for recommending doing the poses as I suggest. Broad generated tremendous publicity for his book by trumpeting the risk of vertebral artery strokes, and made the absurd, entirely unscientific calculation that yoga causes 300 strokes and 15 deaths per year in the U.S. My guess is that it’s more like in a one in a zillion scenario.

Ironically, skillfully practicing the very poses that Broad recommends avoiding might actually lower the risk of the vertebral artery strokes. When you gradually stretch the arteries and surrounding tissues as could be expected with a regular yoga practice, the vessels would likely become more pliable, and resistant to tearing with sudden movement or trauma.

And the bigger picture is that vertebral artery strokes are a tiny percentage of all strokes, estimated to strike 269 people per 100,000 every year. Yoga’s documented ability to lower blood pressure, cholesterol and stress hormones, reduce inflammation, thin the blood, etc., in all likelihood greatly lowers the incidence of all types of strokes—as well as heart attacks and a host of other conditions. Just be sure to be mindful of contraindications. So, for example, if you have poorly controlled high blood pressure, you probably want to avoid inversions like Headstand entirely. The risk of having a stroke as a result is probably small, but it’s better to err on the side of caution.

Follow Yoga for Healthy Aging on Facebook ° To order Yoga for Healthy Aging: A Guide to Lifelong Well-Being, go to Amazon, Shambhala, Indie Bound or your local bookstore.

Very good, Timothy.

Robert Hoyle/Santa Fe.

Lovely and informative post, thank you. Could you do one of the most helpful "Baxter" photos (with or without dog) to show the blanket/shoulder arrangement in more detail? Thanks.

Also read "Practice Awareness" in the Feb 2013 Yoga Journal. What I found very enlightening is that Headstand is usually not taught for the first 2 or 3 years of Yoga practice, if at all, by many senior teachers. Yet the average Yoga teacher pushes people to do headstand, Halasana, and shoulder stand to beginners. Worst part is that only Iyengar teachers use props – blankets, chairs, etc. As much as American Yoga teachers and studios would complain, we need national guidelines for Yoga inversions. That might get resistance from the teachers who are Yoga/Pilates/massage therapist/Qi Kung/Kung fu experts, but that IS part of the problem.

Thanks for sharing this article. I do yoga although not regularly but I have gained some health benefits from it.

Bravo Tim, well done.

I experienced a TSI (mini-stroke) doing yoga just last week. Called 911, who sent EMS to my home. All tests, ECG, etc. looked excellent. So I have a follow-up exam scheduled next month. I love yoga, but I'm a bit nervous to resume my practice.

First learn how to extend spine then learn hypertension.What i see yog students damaging spine & health.

Great but… as a hair dresser for 35 years, the lady tilting her head back into the shampoo bowl is also something some journalist hypothesized. I have seem one instance of a client having a stroke after a shampoo. So I don't think that makes it into something that should be touted as a given.

Very thoughtful article. Broad really did a disservice to yoga in, what I feel, was a blatant pr attempt to sell more books. He's pretty much discredited among educated and informed yogis.

just read Broad's book, _The Science of Yoga_, and Broad is talking with doctors, not yoga teachers. I think you shouldn't portray him as alarmist, and if you can't get another doctor or study to refute the science, you shouldn't speculate that the science is wrong. He's not anti-yoga, and his recommendations are the same as yours: use blankets, be careful not to hyperextend the neck, watch out for plow. As a yoga teacher, he is your ally, not your enemy. I recommend the book to everyone who is doing yoga for aging. Yoga does have fanstastic benefits. But there are specific risks with the neck that everyone should address.

I am researching this subject as I spent an unplanned stay in the ER directly after my second yoga class. First off I am 54 and 40 lbs overweight and was taking this session at my regular gym that I seldom visit. I could not understand the directions due to my poor hearing and the instructors accent. So was constantly straining looks back during poses to keep track. It was a much more advanced class than my first one and poses were very strenuous but I kept trying to the point of failure. Muscles just giving up or too painful. At the end of class during the meditative lie back in the dark and release your tension session, my entire right side of my body felt different from the left and unable to release any tension. Still feeling fine I rolled up my mat and put my shoes on and walked out of the gym with my wife. I commentented about how loose and good I felt but then my right leg became incresingly weak numb and hard to control and then my right arm as well. I was speaking to my wife this whole time about what was happening when it felt like i was beginning to mumble and the right side of my face my face began to feel numb and detatched. I limped and hopped the last several steps to our car and sat down unable to lift my leg into the car. In about a minute or so the facial numbness was gone and my right arm was strong enough to lift my still too weak leg into the car. We drove across the parking lot to urgent care and by this time the attack was completely resolved less some soreness and discomfort in the back my neck.

Urgent care doc could not rule out a TIA aka mini stroke so we went to the ER and after 12 hrs observation and monitoring 2 CAT scans, EKG, MRI and endless stroke field test. The two neurologist who reviewed my test and imaging found nothing wrong except occasionall borderline high blood pressure.

In reading articles concerning the studies you cited my conclusion is that Yoga is fantastic if taught correctly and practiced correctly. If the person practicing yoga for the first time is honest about their abilities and general fitness and does not attempt to exceed themselves there is very little risk of stroke. More importantly new students need proper instruction and to work at their own pace and level of yoga. Spontaneously entering a class at your general fitness gym because it matches your schedule versus you proper experience level can be dangerous.

Since yoga is not regulated, injuries are not reported and poses have not been scientifically evaluated for adverse effects. Broad did a great service to the yoga industry by investigating yoga and the inherent risks or benefits. We have no regulation or real science to back up how the poses are actually affecting the body. Sure we know it can in some cases lower blood pressure and stress etc but as far as the biomechanics, there have not been any real studies I have seen on individual poses like plow. I would say that if you did an X-ray of someone in plow pose, there would definitely be compression and loading of the anterior vertebral structure. Because people can get a stroke from just sudden movements or shampooing, doing plow pose for minutes at a time is way too risky. I have been teaching for over 30 years and I would not practice or instruct anyone to perform shoulderstand, plow or headstand with or without blankets. The cervical spine is not weight bearing and if you continue to load it, there could be bone added to mimic the denser thicker lumbar spine. Ligament laxity as well could occur as micro- tearing of the connective tissue that protects arteries can happen as a result of these inversions. Why take the risk? I know of several people who developed bone spurs from a regular practice of headstand and another woman who had VAD or vertebral artery dissection or mini-strokes that she feels is a result of making her neck too flexible. I think many of your suggestions such as not leading with the head in a spinal rotation or looking up and causing hyper-extension are important however to suggest stretching the neck to prevent injuries or strokes lacks scientific creditability. The cervical spine is not weight bearing and I think that is what we need to honor the natural curves in the neck. I am also a bodyworker and posture educator and have noticed that many people with a long time inversion practice develop a spine that is totally flat with no curves at all ! The entire spine looks like a straight rod and I think that poses like plow could be undoing the necessary tension out of the spinal column and eventually it does not spring back. Tissues have a natural recoiling that can be undone by the tendency in yoga to stretch the spine in all directions. Research from spine experts like Dr. Stuart McGill is revealing that people with the most back pain have a very loose and flexible spine. You can live your whole life and never do plow or shoulderstand and be quite healthy. However doing these poses carries a huge inherent risk that is not worth it in the long run. Flexibility can be a liability. https://www.elephantjournal.com/2013/07/when-flexibility-becomes-a-liability-michaelle-edwards/