by Nina

|

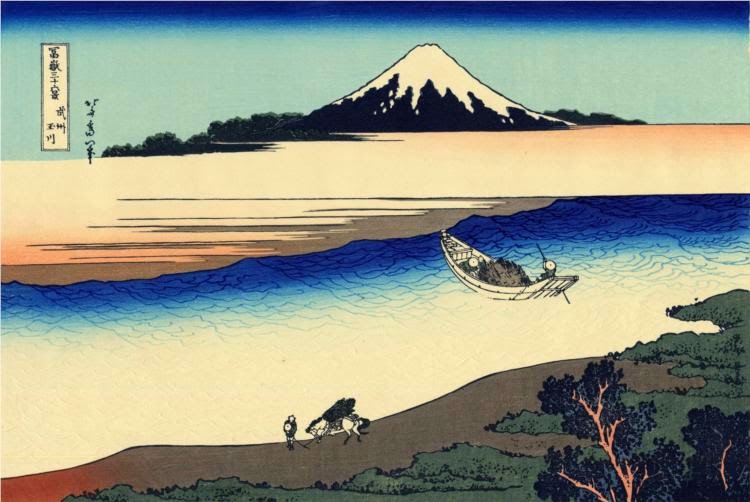

| Tama River in the Musashi Province by Hokusai |

One of the most difficult times in my life—and in my marriage—was when Brad and I were fighting over our future. When our children were small, he wanted the four of us to move to New York City because he was interested in a possible academic position at a university there, and I wanted to stay in Berkeley so I could keep my own job—which felt like a special opportunity to me—stay near my family, and raise our children in a house with a garden rather than a small apartment. Without going into details about our arguments, I’ll just say that our desires for our future were so different that it felt like they were tearing us apart. And I became extremely stressed out and anxious. But here’s the thing: although Brad interviewed for the job he wanted, the university decided not to hire anyone for that position after all. So in the end, all the angst we went through was over nothing. I eventually realized that this was a pattern in our relationship—battling over things that hadn’t happened yet. I also realized I had a tendency to be anxious about possible future scenarios. So after that I came up the following motto for myself: Don’t Panic Too Soon. Believe it or not, just having this simple motto has been quite powerful, and I continue to invoke it to this day.

When Ram wrote his post The Second Branch of Yoga: The Niyamas, we both realized that we don’t have very many articles on the individual niyamas on the blog. Yes, we have a few posts on santosha (Santosha: Happiness and Longevity and Yoga Philosophy: Contentment) but not much else. So I decided to look at the list of niyamas to see if there was one I felt I could write about. It was easy for me to choose because there is one particular niyama that I’ve found especially valuable in my daily life: svadhyaya. In his post, Ram said of svadhyaya:

“The path to self-realization is also through introspection and contemplation of our own life’s lessons. Introspecting about our emotions, thoughts, actions, and reactions helps us to learn about our own self and our true nature. When we reflect on our flaws and allow our mistakes to serve as learning lessons, we have the opportunity to grow.”

In our journeys toward the equanimity that is yoga, we can all benefit from this study of the self. Ram explained that we do so by becoming a witness to our own selves. As a witness, you observe with detachment what’s happening within you—your sensations, thoughts, emotions, and feelings. The Sankrit word sākshī (saa-kshe), refers to the “pure awareness” that witnesses the world but does not get affected by it or involved with it. The term is made up of two parts. “Sa” means “with” and “aksha” means “senses or eyes.” So the sakshi is an awareness that can observe “with its own eyes.” Another meaning of the word aksha is “the center of a wheel.” As the wheel turns, its center remains still. So the witness mind remains steady while events turn around it.

In meditation, your witness mind is essential. Your witness mind observes when your attention has wandered from the object of your meditation—and to what. Rather than floating down the stream of your thoughts, you sit on the shore and impartially observe from a distance (see What is Meditation?). But you can also use your witness mind during your asana practice by cultivating mindfulness (see What is Mindfulness?). To do this, step back and tune into the constant judging and reacting to inner and outer experiences that constantly stream through your mind. In your asana practice, it can be especially illuminating to use this technique when you practice challenging poses or poses you dislike.

Eventually you can use on your witness mind during any activity. In my post Mental Yoga: Thataashut I wrote about using my witness mind when I was trying to write a blog post while construction was going on outside my window. Observing my thought patterns helped me calm down and find some peace of mind even with people arguing outside and making the kind of invasive noise that only large machines are capable of. Observing your habits can help you change the way you react to stress (see Changing the Brain’s Stressful Habits). And it can help you in general to change your patterns of reactivity (see Meditation and Brain Strength). All of this will help you cultivate equanimity in your daily life—not to mention fewer marital battles—and we can all use some of that.

That’s it for today. Svadhyaya actually has two different interpretations, and I was originally going to write about both of them in this post. But I’m starting to feel like I’ve gone on long enough, so I’ve decided to divide the subject into two separate posts. So stay tuned for another post this week on the second interpretation of svadhyaya: study of the scriptures.

Follow Yoga for Healthy Aging on Facebook ° To order Yoga for Healthy Aging: A Guide to Lifelong Well-Being, go to Amazon, Shambhala, Indie Bound or your local bookstore.

Nina,too good yar.