by Baxter

|

| Cloud Study by John Constable |

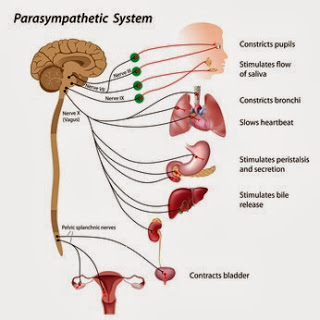

When I read the posts of my fellow YFHA bloggers, I often learn new perspectives that might differ from my own as well as new information that I was previously unaware of. Reading the posts also highlights occasions where I could have been clearer or given better information on a particular topic. As an example, I have written about breath techniques and their effect on the autonomic nervous system, as did Timothy in his awesome follow-up post on the buzzing bee breath, Bhramari Pranayama with Mudras. And we often mention that extending or lengthening the exhalation triggers the parasympathetic nervous system, the Rest and Digest part of our nervous system’s balancing program. This made me realize that I could add a bit more detail to explain how that actually happens.

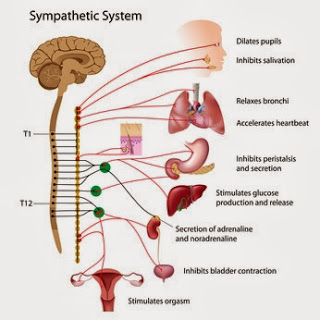

It turns out the Autonomic Nervous System (ANS) that connects brain to body is a two-way street. If I am anxious and nervous or stressed out by events in my life or simply the thoughts about those events, my brain, via the nerves of the ANS, will likely turn on the Sympathetic part of that system (the Fight or Flight response), which could result in faster heart and breathing rates, and increases in blood pressure, to mention just two of the most obvious physiological changes.

But the cool thing is that the lungs and heart can feed back to the brain and essentially convince the brain that things are calm and peaceful, even when there are still stressful circumstances. One neat way this happens involves the relationship of the heart and lungs and the nerves between them. In each round of breath, during your inhalation, your heart gets stimulated to beat a little faster. Then during the exhalation that follows, your heart gets told to slow down a tad. The overall effect is very little change in the heart rate from minute to minute. But when you make one part of the breath cycle, either the inhale or the exhale, longer than the other, and you do this for several minutes, the accumulated effect is that you will either slow the heart rate down or speed it up from where you started. When you make the inhales longer than the exhales, for example, by using a two-second inhale and a one-second exhale, and you keep this up for several minutes, the heart rate will go a bit faster. This will send a feedback message to the brain that things need to activate more in the brain and body for whatever work there is to be done, stimulating the Sympathetic portion of the ANS.

With the very useful Bhramari breath Timothy expanded on Bhramari Breath with Mudras, we do the opposite. As we hum during the exhalation, the exhales get longer relative to the inhales, as when we do a 1:2 ratio breath practice without the humming. This new respiratory cycle begins to slow down the heart rate, sending a message to the brain that everything is more peaceful and calm than five minutes ago, allowing the brain to support this shift further by activating the Parasympathetic portion of the ANS (the Rest and Digest or Relaxation response) that goes back from brain to body.

Research has shown that the vagus nerve as well as certain chemical neurotransmitters account for these effects of breath patterns on heart rate and subsequently on shifting the balance between the Sympathetic and Parasympathetic parts of the ANS. Keep in mind that the ANS is trying to keep all background systems in balance and responding appropriately to ever-changing circumstances of our day.

I’m providing this information for those of you who want to go a bit deeper in your understanding of how breath patterns affect the nervous system balance and either excite the system or quiet it. Our conscious choice of breathing differently can shift us to a more desirable part of the ANS, either by stimulating the active Sympathetic branch or the quieting Parasympathetic branch. Most of us need more of the latter, but not always!

For a little more background on how the Respiratory system influences the Cardiac system, which in turn influences the Autonomic Nervous System, see The human respiratory gate as well as Effects of yoga on the autonomic nervous system, gamma-aminobutyric-acid, and allostasis in epilepsy, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Follow Yoga for Healthy Aging on Facebook ° To order Yoga for Healthy Aging: A Guide to Lifelong Well-Being, go to Amazon, Shambhala, Indie Bound or your local bookstore.

Hi Baxter!

Thanks for your well written extremely informative yet terse blog updates. You are providing an excellent resource for yogis all over the world.

Denise in Paris

This explains what I've been reading about so well! It is such a well known fact that yoga can help us relax and "de-stress". It's always nice as a yoga teacher to know a little of the science behind it. thank you so much!

Dear Esteemed Drs,

I am teaching a Pranayama workshop and linking it to Brain Physiology. I checked this article and I am confused. According to your article, inhalation stimulates the SNS (sympathetic nervous system) and exhalation triggers PNS (parasympathetic nervous system). Is this your personal experience or are you pretty sure about this correlation because I did not find this in any Yoga textbooks or articles.

Just think about Kapalabhati Pranayama: The inhalation is very passive and exhalation is very forceful. If your correlation is true, at the end of Kapalabhati pranayama, you need to feel more relaxed and calm (exhalation-PNS). But this is not what we typically experience. The nature of Kapalabhati pranayama is such that it makes an individual more active, there is more heat generated in mind and body and it awakens an individual from stupor. I guess this is due to activation of SNS. So this would be contradictory to what you mentioned. What is the correct explanation? Namaste!!!